Fill Out Your Development Lifespan 6Th Edition Form

The Development Lifespan 6th Edition form, authored by Laura E. Berk, provides a comprehensive guide to the cognitive development of infants and toddlers, emphasizing the crucial early years of life. This edition highlights key theories, particularly focusing on the work of renowned Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, whose ideas about cognitive change have shaped our understanding of how children learn and grow. Central to this exploration are the stages of cognitive development, particularly the sensorimotor stage, where children transition from reflexive actions to purposeful behavior. The form also dives into infant language development, examining how the emergence of first words coincides with cognitive milestones. In addition, it investigates varied influences on early development, such as culture and social context, and considers the assessment tools designed to measure intellectual progress in young children. These aspects collectively aim to paint a clearer picture of the remarkable transformations that occur during early childhood and the pivotal role caregivers play in supporting this growth. Through a detailed exploration of cognitive theories, practical observations, and educational implications, this form seeks to inform and empower parents, educators, and researchers alike.

Development Lifespan 6Th Edition Example

Development Through

the Lifespan, 6/e

Laura E. Berk

©2014 / ISBN: 9780205957606

Chapter begins on next page >

PLEASE NOTE: This sample chapter was prepared in advance of book publication. Additional changes may appear in the published book.

To request an examination copy or for additional information, please visit us at www.pearsonhighered.com or contact your Pearson representative at www.pearsonhighered.com/replocator.

c h a p t e r 5

© KRISTIN DUVALL/GETTY IMAGES

A father encourages his child’s curiosity and delight in discovery. With the sensitive support of caring adults, infants’ and toddlers’ cognition and language develop rapidly.

150

Cognitive

Development

in Infancy and

Toddlerhood

When Caitlin, Grace, and Timmy gathered at Ginette’s child‐care

home, the playroom was alive with activity. The three spirited

explorers, each nearly 18 months old, were bent on discovery. Grace dropped shapes through holes in a plastic box that Ginette held and

adjusted so the harder ones would fall smoothly into place. Once a few shapes were inside, Grace grabbed the box and shook it, squealing with delight as the lid fell open and the shapes scattered around her. The clatter attracted Timmy, who picked up a shape, carried it to the railing at the top of the basement steps, and dropped it overboard, then followed with a teddy bear, a ball, his shoe, and a spoon. Meanwhile, Caitlin pulled open a drawer, unloaded a set of wooden bowls, stacked them in a pile, knocked it over, and then banged two bowls together.

As the toddlers experimented, I could see the beginnings of spoken language— a whole new way of influencing the world. “All gone baw!” Caitlin exclaimed as Timmy tossed the bright red ball down the basement steps. “Bye‐bye,” Grace chimed in, waving as the ball disappeared from sight. Later that day, Grace

revealed the beginnings of make‐believe. “Night‐night,” she said, putting her head down and closing her eyes, ever so pleased that she could decide for herself when and where to go to bed.

Over the first two years, the small, reflexive new born baby becomes a self‐assertive, purposeful being who solves simple problems and starts to master the most amazing human ability: language. Parents wonder, how does all this happen so quickly? This question has also captivated researchers, yielding a wealth of findings along with vigorous debate over how to explain the astonishing pace of infant and toddler cognition.

In this chapter, we take up three perspectives on early cognitive development: Piaget’s cognitive‐developmental theory, information processing, and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory. We also consider the usefulness of tests that measure infants’ and toddlers’ intellectual progress. Finally, we look at the beginnings of language. We will see how toddlers’ first words build on early cognitive achievements and how, very soon, new words and expressions greatly increase the speed and flexibility of their thinking. Throughout development, cognition and language mutually support each other. ●

c h a p t e r o u t l i n e

Piaget’s Cognitive‐Developmental Theory

Piaget’s Ideas About Cognitive Change • The Sensorimotor Stage • Follow‐Up Research on Infant Cognitive Development • Evaluation of the Sensorimotor Stage

■SoCial iSSueS: eDuCaTion Baby Learning

from TV and Video: The Video Deficit Effect

information Processing

A General Model of Information Processing •

Attention • Memory • Categorization •

Evaluation of Information‐Processing

Findings

■Biology anD environmenT Infantile Amnesia

The Social Context of early Cognitive Development

■CulTural influenCeS Social Origins of Make‐Believe Play

individual Differences in early mental Development

Infant and Toddler Intelligence Tests • Early Environment and Mental Development • Early Intervention for At‐Risk Infants and Toddlers

language Development

Theories of Language Development • Getting Ready to Talk • First Words • The Two‐Word Utterance Phase • Individual and Cultural Differences • Supporting Early Language Development

151

152PART III Infancy and Toddlerhood: The First Two Years

Piaget’s Cognitive‐

Piaget’s Cognitive‐  Developmental Theory

Developmental Theory

Swiss theorist Jean Piaget inspired a vision of children as busy, motivated explorers whose thinking develops as they act directly on the environment. Influenced by his background in biology, Piaget believed that the child’s mind forms and modi fies psychological structures so they achieve a better fit with external reality. Recall from Chapter 1 that in Piaget’s theory, children move through four stages between infancy and adoles cence. During these stages, all aspects of cognition develop in an integrated fashion, changing in a similar way at about the same time.

Piaget’s first stage, the sensorimotor stage, spans the first two years of life. Piaget believed that infants and toddlers “think”

with their eyes, ears, hands, and other sensorimotor equipment. They cannot yet carry out many activities inside their heads. But by the end of toddlerhood, children can solve practical, everyday problems and represent their experiences in speech, gesture, and play. To appreciate Piaget’s view of how these vast changes take place, let’s consider some important concepts.

Piaget’s Ideas About Cognitive Change

According to Piaget, specific psychological

In Piaget’s theory, two processes, adaptation and organiza- tion, account for changes in schemes.

Adaptation. Take a MoMenT… The next time you have a chance, notice how infants and toddlers tirelessly repeat ac tions that lead to interesting effects. Adaptation involves build ing schemes through direct interaction with the environment. It consists of two complementary activities, assimilation and accommodation. During assimilation, we use our current schemes to interpret the external world. For example, when Timmy dropped objects, he was assimilating them to his senso rimotor “dropping scheme.” In accommodation, we create new schemes or adjust old ones after noticing that our current ways of thinking do not capture the environment completely. When Timmy dropped objects in different ways, he modified his drop ping scheme to take account of the varied properties of objects.

According to Piaget, the balance between assimilation and accommodation varies over time. When children are not changing

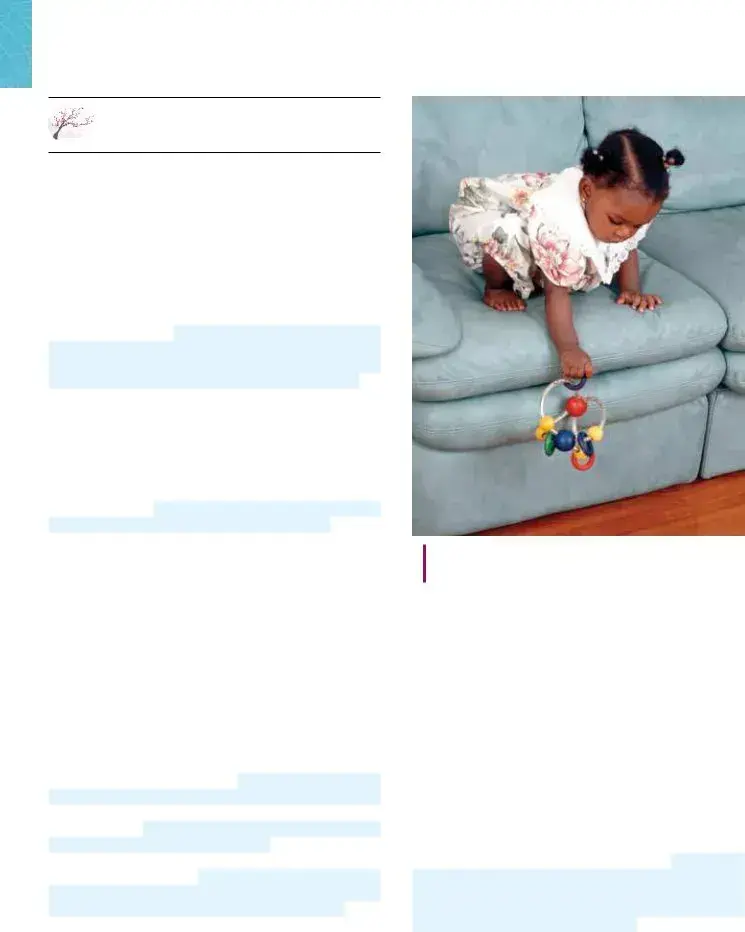

© LAURA DWIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY

In Piaget’s theory, first schemes are sensorimotor action patterns. As this

much, they assimilate more than they

Each time this back‐and‐forth movement between equil ibrium and disequilibrium occurs, more effective schemes are produced. Because the times of greatest accommodation are the earliest ones, the sensorimotor stage is Piaget’s most complex period of development.

Organization. Schemes also change through organization, a process that takes place internally, apart from direct contact with the environment. Once children form new schemes, they rearrange them, linking them with other schemes to create a strongly interconnected cognitive system. For example, even tually Timmy will relate “dropping” to “throwing” and to his developing understanding of “nearness” and “farness.” According to Piaget, schemes truly reach equilibrium when they become

CHAPTER 5 Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood |

153 |

part of a broad network of structures that can be jointly applied to the surrounding world (Piaget, 1936/1952).

In the following sections, we will first describe infant development as Piaget saw it, noting research that supports his observations. Then we will consider evidence demonstrating that, in some ways, babies’ cognitive competence is more advanced than Piaget believed.

The Sensorimotor Stage

The difference between the newborn baby and the 2‐year‐ old child is so vast that Piaget divided the sensorimotor stage into six substages, summarized in Table 5.1. Piaget based this sequence on his own three

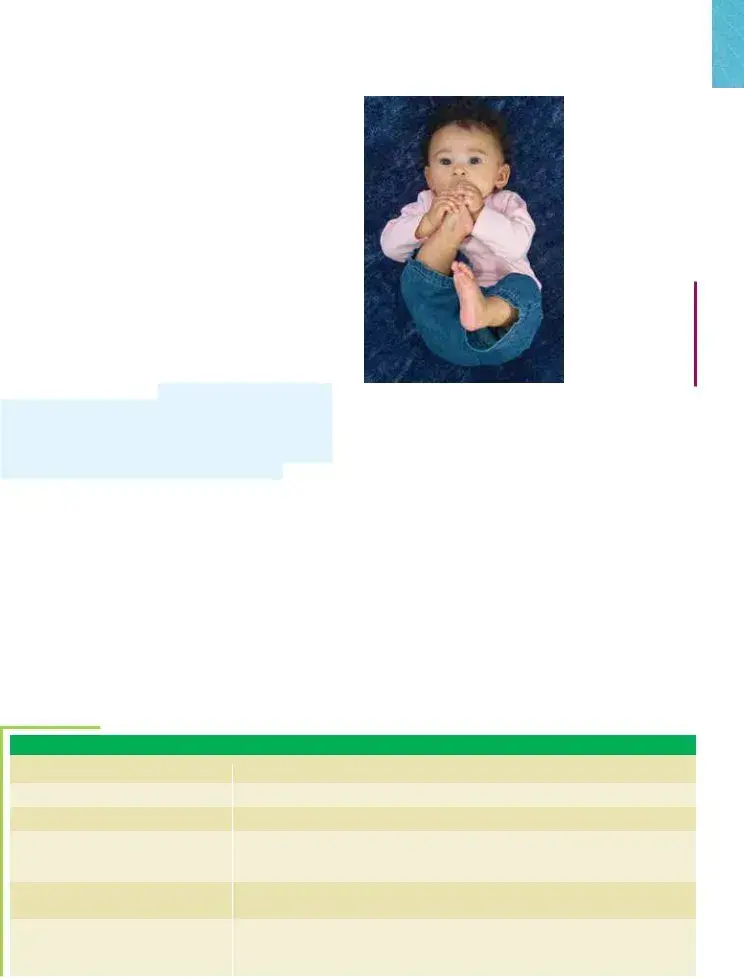

According to Piaget, at birth infants know so little that they cannot explore purposefully. The circular reaction provides a special means of adapting their first schemes. It involves stum bling onto a new experience caused by the baby’s own motor

activity. The reaction is “circular” because, as the infant tries to repeat the event again and again, a sensorimotor response that first occurred by chance strengthens into a new scheme. Consider Caitlin, who at age 2 months accidentally made a smacking noise after a feeding. Finding the sound intriguing, she tried to repeat it until she became quite expert at smacking her lips.

The circular reaction initially centers on the infant’s own body but later turns outward, toward manipulation of objects. In the second year, it becomes experimental and creative, aimed at producing novel outcomes. Infants’ difficulty inhibiting new and interesting behaviors may underlie the circular reaction. This immaturity in inhibition seems to be adaptive, helping to ensure that new skills will not be interrupted before they strengthen (Carey & Markman, 1999). Piaget considered revi sions in the circular reaction so important that, as Table 5.1 shows, he named the sensorimotor substages after them.

© ELLEN B. SENISI PHOTOGRAPHY

This

Repeating Chance behaviors. Piaget saw newborn reflexes as the building blocks of sensorimotor intelligence. In Substage 1, babies suck, grasp, and look in much the same way, no matter what experiences they encounter. In one amusing example, Carolyn described how 2‐week‐old Caitlin lay on the bed next to her sleeping father. Suddenly, he awoke with a start. Caitlin had latched on and begun to suck on his back!

Around 1 month, as babies enter Substage 2, they start to gain voluntary control over their actions through the primary circular reaction, by repeating chance behaviors largely moti vated by basic needs. This leads to some simple motor habits, such as sucking their fist or thumb. Babies in this substage also begin to vary their behavior in response to environmental demands. For example, they open their mouths differently for a nipple than for a spoon. And they start to anticipate events. When hungry, 3‐month‐old Timmy would stop crying as soon as Vanessa entered the

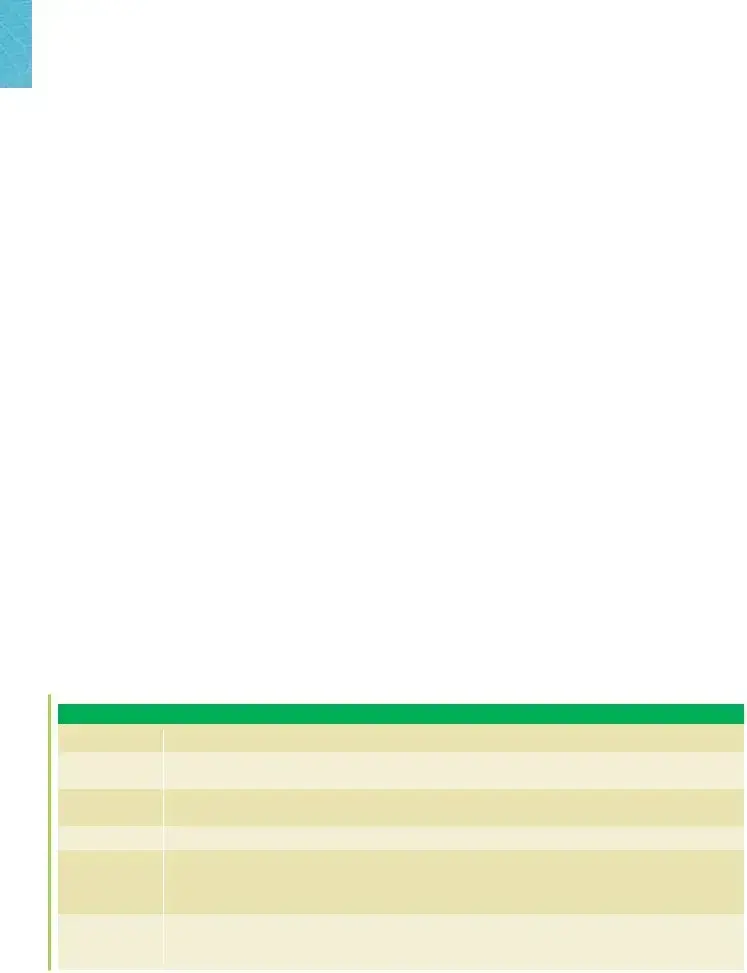

TAblE 5.1

Summary of Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage

SenSorImoTor SubSTAge

1.Reflexive schemes

2.Primary circular reactions

3.Secondary circular reactions

4.Coordination of secondary circular reactions

5.Tertiary circular reactions

6.Mental representation (18

TyPICAl ADAPTIve behAvIorS

Newborn reflexes (see Chapter 3, page 107)

Simple motor habits centered around the infant’s own body; limited anticipation of events

Actions aimed at repeating interesting effects in the surrounding world; imitation of familiar behaviors

Intentional, or goal‐directed, behavior; ability to find a hidden object in the first location in which it is hidden (object permanence); improved anticipation of events; imitation of behaviors slightly different from those the infant usually performs

Exploration of the properties of objects by acting on them in novel ways; imitation of novel behaviors; ability to search in several locations for a hidden object (accurate

Internal depictions of objects and events, as indicated by sudden solutions to problems; ability to find an object that has been moved while out of sight (invisible displacement); deferred imitation; and make‐believe play

154PART III Infancy and Toddlerhood: The First Two Years

During Substage 3, from 4 to 8 months, infants sit up and reach for and manipulate objects. These motor achievements strengthen the secondary circular reaction, through which babies try to repeat interesting events in the surrounding environment that are caused by their own actions. For example, 4‐month‐old Caitlin accidentally knocked a toy hung in front of her, pro ducing a fascinating swinging motion. Over the next three days, Caitlin tried to repeat this effect, gradually forming a new “hitting” scheme. Improved control over their own behavior permits infants to imitate others’ behavior more effectively. However, they usually cannot adapt flexibly and quickly enough to imitate novel behaviors. Therefore, although they enjoy watching an adult demonstrate a game of pat‐a‐cake, they are not yet able to participate.

Intentional behavior. In Substage 4, 8‐ to 12‐month‐ olds combine schemes into new, more complex action sequences. As a result, actions that lead to new schemes no longer have a hit‐or‐miss

Retrieving hidden objects reveals that infants have begun to master object permanence, the understanding that objects continue to exist when out of sight. But this awareness is not yet complete. Babies still make the A‐not‐B search error: If they reach several times for an object at a first hiding place (A), then see it moved to a second (B), they still search for it in the first

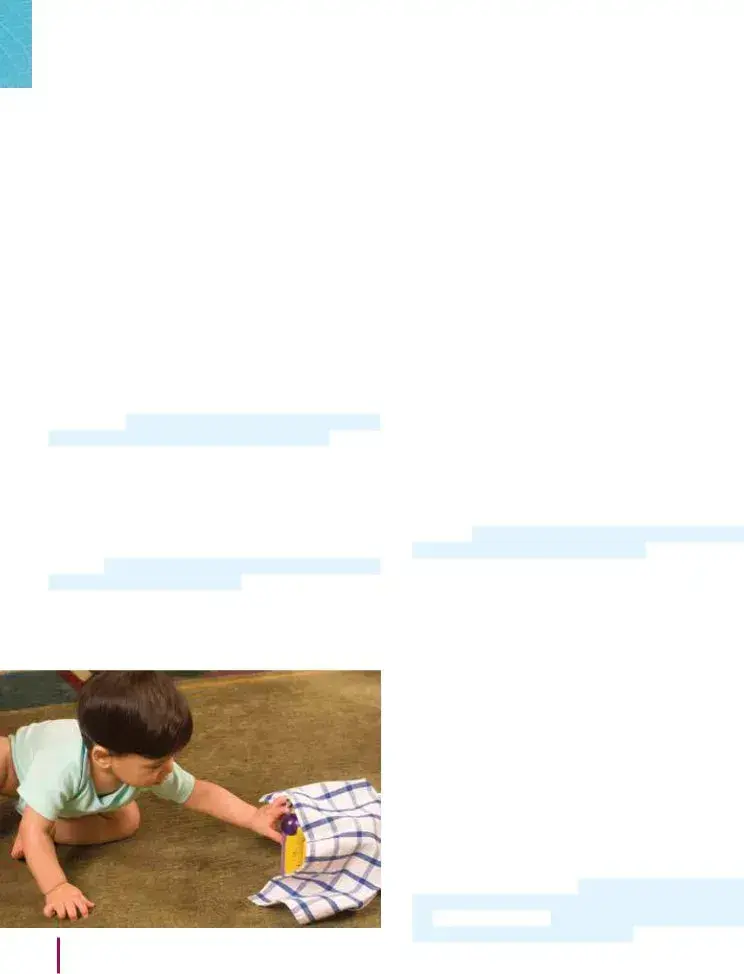

© LAURA DWIGHT/PHOTOEDIT

To find the toy hidden under the cloth, a

hiding place (A). Consequently, Piaget concluded, they do not have a clear image of the object as persisting when hidden from view.

Infants in Substage 4, who can better anticipate events, sometimes use their capacity for intentional behavior to try to change those events. At 10 months, Timmy crawled after Vanessa when she put on her coat, whimpering to keep her from leaving. Also, babies can now imitate behaviors slightly different from those they usually perform. After watching someone else, they try to stir with a spoon, push a toy car, or drop raisins into a cup (Piaget, 1945/1951).

In Substage 5, from 12 to 18 months, the tertiary circular reaction, in which toddlers repeat behaviors with variation, emerges. Recall how Timmy dropped objects over the base ment steps, trying first this action, then that, then another. This deliberately exploratory approach makes 12‐ to 18‐month‐olds better problem solvers. For example, Grace figured out how to fit a shape through a hole in a container by turning and twisting it until it fell through and how to use a stick to get toys that were out of reach. According to Piaget, this capacity to experiment leads to a more advanced understanding of object permanence. Toddlers look for a hidden toy in several locations, displaying an accurate

Mental Representation. Substage 6 brings the ability to create mental

Piaget noted that 18‐ to 24‐month‐olds arrive at solutions suddenly rather than through trial‐and‐error behavior. In doing so, they seem to experiment with actions inside their heads— evidence that they can mentally represent their experiences. For example, at 19 months,

Representation also enables older toddlers to solve advanced object permanence problems involving invisible displacement— finding a toy moved while out of sight, such as into a small box while under a cover. It permits deferred

CHAPTER 5 Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood |

155 |

Follow‐up research on Infant Cognitive Development

Many studies suggest that infants display a wide array of under standings earlier than Piaget believed. Recall the operant con ditioning research reviewed in Chapter 4, in which newborns sucked vigorously on a nipple to gain access to interesting sights and sounds. This behavior, which closely resembles Piaget’s secondary circular reaction, shows that infants explore and con trol the external world long before 4 to 8 months. In fact, they do so as soon as they are born.

To discover what infants know about hidden objects and other aspects of physical reality, researchers often use the violation‐of‐expectation method. They may habituate babies to a physical event (expose them to the event until their looking declines) to familiarize them with a situation in which their knowledge will be tested. Or they may simply show babies an

expected event (one that follows physical laws) and an unexpected event (a variation of the first event that violates physical laws). Heightened attention to the unexpected event suggests that the infant is “surprised” by a deviation from physical reality and, therefore, is aware of that aspect of the physical world.

The violation‐of‐expectation method is controversial. Some researchers believe that it indicates limited awareness of phys ical

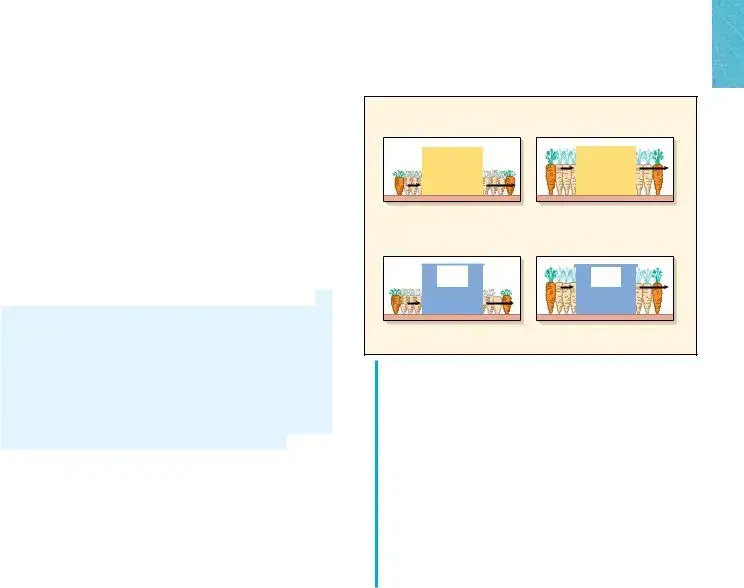

Object Permanence. In a series of studies using the violation‐of‐expectation method, Renée Baillargeon and her collaborators claimed to have found evidence for object per manence in the first few months of life. Figure 5.1 illustrates one of these studies (Aguiar & Baillargeon, 2002; Baillargeon

&DeVos, 1991). After habituating to a short and a tall carrot moving behind a screen, infants were given two test events:

(1) an expected event, in which the short carrot moved behind a screen, could not be seen in its window, and reappeared on the other side; and (2) an unexpected event, in which the tall carrot moved behind a screen, could not be seen in its win dow (although it was taller than the window’s lower edge), and reappeared. Infants as young as 2½ to 3½ months looked longer at the unexpected event, suggesting that they had some awareness that an object moved behind a screen would continue to exist.

Additional violation‐of‐expectation studies yielded simi lar results, suggesting that infants look longer at a wide variety of unexpected events involving hidden objects (Newcombe, Sluzenski, & Huttenlocher, 2005; Wang, Baillargeon, & Paterson, 2005). Still, several researchers using similar procedures failed to confirm Baillargeon’s findings (Cohen & Marks, 2002; Schöner

&Thelen, 2006; Sirois & Jackson, 2012). And, as previously

Habituation Events |

|

|

(a) |

|

Test Events |

Expected event |

Unexpected event |

(b) |

(c) |

FIguRE 5.1 Testing young infants for understanding of object permanence using the violation‐of‐expectation method.

(a)First, infants were habituated to two events: a short carrot and a tall carrot moving behind a yellow screen, on alternate trials. Next, the researchers presented two test events. The color of the screen was changed to help infants notice its window. (b) In the expected event, the carrot shorter than the window’s lower edge moved behind the blue screen and reappeared on the other side.

(c)In the unexpected event, the carrot taller than the window’s lower edge moved behind the screen and did not appear in the window, but then emerged intact on the other side. Infants as young as 2½ to 3½ months looked longer at the unexpected event, suggesting that they had some understanding of object permanence. (Adapted from R. Baillargeon & J. DeVos, 1991, “Object Permanence in Young Infants: Further Evidence,” Child Development, 62, p. 1230. © 1991, John Wiley and Sons. Adapted with permission of John Wiley and Sons.)

noted, critics question what babies’ looking preferences tell us about what they actually understand.

But another type of looking behavior suggests that young infants are aware that objects persist when out of view. Four‐ and 5‐month‐olds will track a ball’s path of movement as it disappears and reappears from behind a barrier, even gazing ahead to where they expect it to emerge (Bertenthal, Longo, & Kenny, 2007; Rosander & von Hofsten, 2004). With age, babies are more likely to fixate on the predicted place of the ball’s reap pearance and wait for

In related research, 6‐month‐olds’ ERP brain‐wave activity was recorded as the babies watched two events on a computer screen. In one event, a black square moved until it covered an object, then moved away to reveal the object (object perma nence). In the other, as a black square began to move across an object, the object disintegrated (object disappearance) (Kaufman, Csibra, & Johnson, 2005). Only while watching the first event did the infants show a particular brain‐wave pattern in the right temporal

If young infants do have some notion of object permanence, how do we explain Piaget’s finding that even babies capable

156PART III Infancy and Toddlerhood: The First Two Years

of reaching do not try to search for hidden objects before 8 months of age? Consistent with Piaget’s theory, searching for hidden objects is a true cognitive advance because infants solve some object‐hiding tasks before others: Ten‐month‐olds search for an object placed on a table and covered by a cloth before they search for an object that a hand deposits under a cloth (Moore

&Meltzoff, 1999). In the second, more difficult task, infants seem to expect the object to reappear in the hand from which it initially disappeared. When the hand emerges without the object, they conclude that there is no other place the object could be. Not until 14 months can most babies infer that the hand deposited the object under the cloth.

Once 8‐ to 12‐month‐olds search for hidden objects, they make the A‐not‐B search error. Some research suggests that they search at A (where they found the object previously) instead of B (its most recent location) because they have trouble inhibit ing a previously rewarded response (Diamond, Cruttenden, & Neiderman, 1994). Another possibility is that after finding the object several times at A, they do not attend closely when it is hidden at B (Ruffman & Langman, 2002).

A more comprehensive explanation is that a complex, dynamic system of

lOOk AnD lIsTEn

Using an attractive toy and cloth, try several object‐hiding tasks with 8‐ to 14‐month‐olds. Is their searching behavior consistent with research findings? ●

In sum, mastery of object permanence is a gradual achieve ment. Babies’ understanding becomes increasingly complex with age: They must distinguish the object from the barrier concealing it, keep track of the object’s whereabouts, and use this knowledge to obtain the object (Cohen & Cashon, 2006; Moore & Meltzoff, 2008). Success at object search tasks coin cides with rapid development of the frontal lobes of the cerebral cortex (Bell, 1998). Also crucial are a wide variety of experiences perceiving, acting on, and remembering objects.

Mental Representation. In Piaget’s theory, before about 18 months of age, infants are unable to mentally represent experience. Yet 8‐ to 10‐month‐olds’ ability to recall the location of hidden objects after delays of more than a minute, and 14‐ month‐olds’ recall after delays of a day or more, indicate that babies construct mental representations of objects and their whereabouts (McDonough, 1999; Moore & Meltzoff, 2004). And in studies of deferred imitation and problem solving, rep resentational thought is evident even earlier.

Deferred and Inferred Imitation. Piaget studied imitation by noting when his three children demonstrated it in their everyday behavior. Under these conditions, a great deal must be known about the infant’s daily life to be sure that deferred

Laboratory research suggests that deferred imitation is present at 6 weeks of age! Infants who watched an unfamiliar adult’s facial expression imitated it when exposed to the same adult the next day (Meltzoff & Moore, 1994). As motor capaci ties improve, infants copy actions with objects. In one study, an adult showed 6‐ and 9‐month‐olds a novel series of actions with a puppet: taking its glove off, shaking the glove to ring a bell inside, and replacing the glove. When tested a day later, infants who had seen the novel actions were far more likely to imitate them (see Figure 5.2). And when researchers paired a second, motionless puppet with the first puppet a day before the dem onstration, 6‐month‐olds generalized the novel actions to this new, very different‐looking puppet (Barr, Marrott, & Rovee‐ Collier, 2003).

Between 12 and 18 months, toddlers use deferred imitation skillfully to enrich their range of sensorimotor schemes. They retain modeled behaviors for at least several months, copy the actions of peers as well as adults, and imitate across a change in

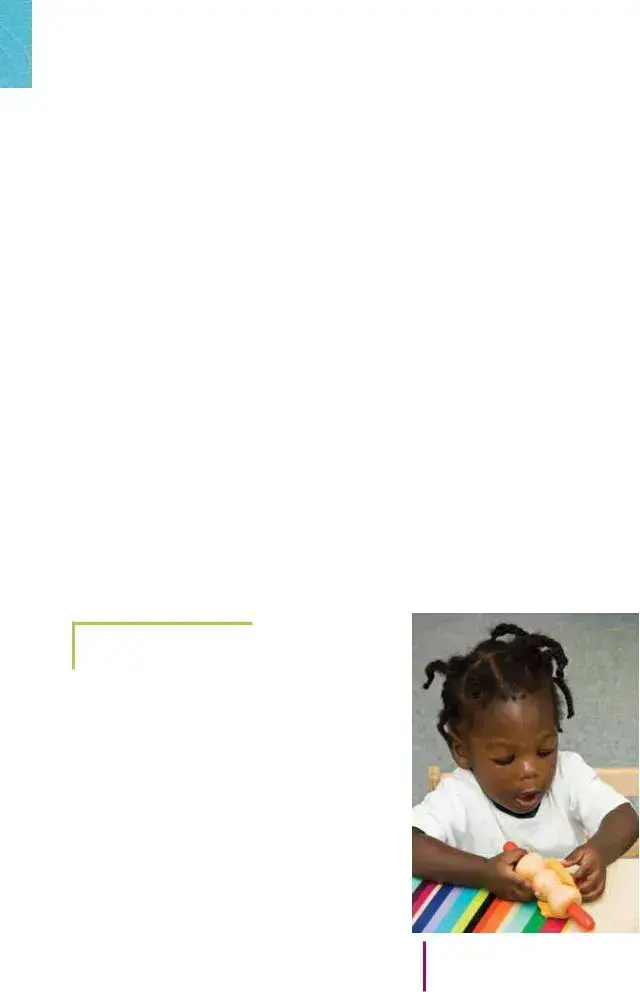

© ELLEN B. SENISI PHOTOGRAPHY

Through deferred imitation, toddlers greatly expand their sensorimotor schemes. While imitat- ing, this

COURTESY Of CAROLYN

CHAPTER 5 Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood |

157 |

FIguRE 5.2 Testing infants for deferred imitation. After researchers performed a novel series of actions with a puppet, this 6‐month‐old imitated the actions a day

(a) |

(b) |

Toddlers even imitate rationally, by inferring others’ inten tions! Fourteen‐month‐olds are more likely to imitate purpose ful than accidental behaviors (Carpenter, Akhtar, & Tomasello, 1998). And they adapt their imitative acts to a model’s goals. If 12‐month‐olds see an adult perform an unusual action for fun (make a toy dog enter a miniature house by jumping through the chimney, even though its door is wide open), they copy the behavior. But if the adult engages in the odd behavior because she must (she makes the dog go through the chimney only after first trying to use the door and finding it locked), 12‐month‐ olds typically imitate the more efficient action (putting the dog through the door) (Schwier et al., 2006).

Between 14 and 18 months, toddlers become increasingly adept at imitating actions an adult tries to produce, even if these are not fully realized (Bellagamba, Camaioni, & Colonnesi, 2006; Olineck & Poulin‐Dubois, 2007, 2009). On one occasion, Ginette attempted to pour some raisins into a bag but missed, spilling them onto the counter. A moment later, Grace began dropping the raisins into the bag, indicating that she had inferred Ginette’s goal.

Problem Solving. As Piaget indicated, around 7 to 8 months, infants develop intentional

By 10 to 12 months, infants can solve problems by analogy— apply a solution strategy from one problem to other relevant problems. In one study, babies were given three similar problems, each requiring them to overcome a barrier, grasp a string, and pull it to get an attractive toy. The problems differed in many aspects of their superficial

with a spoon in the same orientation (handle to one side) readily adapted their motor actions when the spoon was presented with the handle to the other side, successfully transporting food to their mouths most of the time (McCarty & Keen, 2005).

These findings reveal that at the end of the first year, infants form flexible mental representations of how to use tools to get objects. They have some ability to move beyond trial‐and‐error experimentation, represent a solution mentally, and use it in new contexts.

Symbolic Understanding. One of the most momentous early attainments is the realization that words can be used to cue mental images of things not physically

capacity called displaced reference that emerges around the first birthday. It greatly expands toddlers’ capacity to learn about the world through communicating with others. Observations of 12‐month‐olds reveal that they respond to the label of an absent toy by looking at and gesturing toward the spot where it usually rests (Saylor, 2004). As memory and vocabulary improve, skill at displaced reference expands.

But at first, toddlers have difficulty using language to acquire new information about an absent

Awareness of the symbolic function of pictures also emerges in the second year. Even newborns perceive a relation between a picture and its referent, as indicated by their preference for looking at a photo of their mother’s face (see page 145 in Chap ter 4). At the same time, infants do not treat pictures as symbols.

158PART III Infancy and Toddlerhood: The First Two Years

Rather, they touch, rub, and pat a color photo of an object, |

within Piaget’s time frame. Yet other |

||

or pick it up and manipulate it. These behaviors, which reveal |

ondary circular reactions, understanding of object properties, |

||

confusion about the picture’s true nature, decline after 9 months, |

first signs of object permanence, deferred imitation, problem |

||

becoming rare around 18 months (DeLoache et al., 1988; |

solving by analogy, and displaced reference of |

||

DeLoache & Ganea, 2009). |

earlier than Piaget expected. These findings show that the |

||

As long as pictures strongly resemble real objects, by the |

cognitive attainments of infancy do not develop together in the |

||

middle of the second year toddlers treat them symbolically. After |

neat, stepwise fashion that Piaget assumed. |

||

hearing a novel label (“blicket”) applied to a color photo of an |

Recent research raises questions about Piaget’s view of how |

||

unfamiliar object, most 15‐ to |

infant development takes place. Consistent with Piaget’s ideas, |

||

with both the real object and its picture and asked to indicate |

sensorimotor action helps infants construct some forms of |

||

the |

knowledge. For example, in Chapter 4, we saw that crawling |

||

the real object or both the object and its picture, not the picture |

enhances depth perception and ability to find hidden objects, |

||

alone (Ganea et al., 2009). Around this time, toddlers increas |

and handling objects fosters awareness of object properties. Yet |

||

ingly use pictures as vehicles for communicating with others and |

we have also seen that infants comprehend a great deal before |

||

acquiring new knowledge (Ganea, Bloom Pickard, & DeLoache, |

they are capable of the motor behaviors that Piaget assumed led |

||

2008). They point to, name, and talk about pictures, and they can |

to those understandings. How can we account for babies’ amaz |

||

apply something learned from a book with realistic‐looking |

ing cognitive accomplishments? |

||

pictures to real objects, and vice versa. |

|

||

But even after coming to appreciate the symbolic nature |

Alternative Explanations. Unlike Piaget, who thought |

||

of pictures, young children have difficulty grasping the distinc |

young babies constructed all mental representations out of |

||

tion between some pictures (such as line drawings) and their |

sensorimotor activity, most researchers now believe that |

||

referents, as we will see in Chapter 8. How do infants and tod |

infants have some built‐in cognitive equipment for making |

||

dlers interpret another ever‐present, pictorial |

sense of experience. But intense disagreement exists over the |

||

Turn to the Social Issues: Education box on the following page |

extent of this initial understanding. As we have seen, much |

||

to find out. |

|

evidence on young infants’ cognition rests on the violation‐of‐ |

|

|

|

expectation method. Researchers who lack confidence in this |

|

evaluation of the Sensorimotor Stage |

method argue that babies’ cognitive starting point is limited |

||

(Campos et al., 2008; Cohen, 2010; Cohen & Cashon, 2006; |

|||

|

|

||

Table 5.2 summarizes the remarkable cognitive attainments |

Kagan, 2008). For example, some believe that newborns begin |

||

we have just considered. Take a MoMenT… Compare this |

life with a set of biases for attending to certain information and |

||

table with Piaget’s description of the sensorimotor substages in |

with general‐purpose learning |

||

Table 5.1 on page 153. You will see that infants anticipate events, |

techniques for analyzing complex perceptual information. |

||

actively search for hidden objects, master the |

Together, these capacities enable infants to construct a wide |

||

flexibly vary their sensorimotor schemes, engage in make‐ |

variety of schemes (Bahrick, 2010; Huttenlocher, 2002; Quinn, |

||

believe play, and treat pictures and video images symbolically |

2008; Rakison, 2010). |

||

TAblE 5.2 |

Some Cognitive Attainments of Infancy and Toddlerhood |

||

|

|||

Age |

CognITIve ATTAInmenTS |

|

|

18

Secondary circular reactions using limited motor skills, such as sucking a nipple to gain access to interesting sights and sounds

Awareness of object permanence, object solidity, and gravity, as suggested by violation‐of‐expectation findings; deferred imitation of an adult’s facial expression over a short delay (one day)

Improved knowledge of object properties and basic numerical knowledge, as suggested by violation‐of‐expectation findings; deferred imitation of an adult’s novel actions on objects over a short delay (one to three days)

Ability to search for a hidden object when covered by a cloth; ability to solve simple problems by analogy to a previous problem

Ability to search in several locations for a hidden object, when a hand deposits it under a cloth, and when it is moved from one location to another (accurate

Ability to find an object moved while out of sight (invisible displacement); deferred imitation of actions an adult tries to produce, even if these are not fully realized; deferred imitation of everyday behaviors in make‐believe play; beginning awareness of pictures and video as symbols of reality

Take a MoMenT… Which of the capacities listed in the table indicate that mental representation emerges earlier than Piaget believed?

Form Characteristics

| Fact Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Author Information | Development Through the Lifespan, 6th Edition is authored by Laura E. Berk and was published in 2014. |

| ISBN Number | The ISBN for the textbook is 9780205957606. |

| Publication Note | This sample chapter was prepared prior to the book's publication; additional changes may occur in the final version. |

| Developmental Focus | The chapter emphasizes cognitive development in infants and toddlers, showcasing how supportive adults play a crucial role. |

| Piaget’s Theory | The text discusses Piaget’s cognitive-developmental theory, detailing stages that children pass through from infancy to adolescence. |

| Sensorimotor Stage | Piaget's sensorimotor stage lasts from birth to two years, during which infants learn through their senses and actions. |

| Language Development | The book explores how cognitive advancements in infants and toddlers contribute to early language development. |

| Requesting Information | For additional details or to request an examination copy, readers can visit www.pearsonhighered.com. |

Guidelines on Utilizing Development Lifespan 6Th Edition

Following these steps will allow for the accurate completion of the Development Lifespan 6th Edition form. Each step is designed to guide users through the form systematically, ensuring that all necessary information is collected and documented correctly.

- Read through the entire form before beginning to understand all required sections.

- Gather necessary information, including personal details such as name, age, and relevant history, that will be needed to fill out the form.

- Start with your personal details. Fill in your full name in the designated field.

- Indicate your age in the appropriate section. Be sure to use the correct format provided on the form.

- Provide background information as prompted. This may include educational history, relevant experiences, or other pertinent details.

- Complete any additional sections that require information about relationships, health status, or developmental milestones.

- Review the completed form thoroughly. Check for accuracy and completeness to ensure all sections are filled out appropriately.

- Submit the form as per the instructions given, whether electronically or in a physical format, depending on the requirements.

Once the form is filled out, individuals can proceed accordingly, whether it involves submitting it for evaluation or using it as part of a larger assessment process. Careful attention to detail during the completion stage can enhance the utility of the information provided.

What You Should Know About This Form

What is the Development Lifespan 6Th Edition form?

The Development Lifespan 6Th Edition form is an educational resource that outlines the cognitive development of individuals from infancy through toddlerhood. It is designed based on Laura E. Berk's text and includes insights into various developmental theories, including those of Piaget, information processing, and Vygotsky.

How is the content structured in the Development Lifespan 6Th Edition form?

The content is organized thematically, covering key developmental stages, theories, and significant concepts that influence cognitive development. Each section highlights important information on cognitive milestones, language development, and the roles of social and cultural influences in early learning.

Who is the intended audience for this form?

This form is intended for educators, researchers, and students in psychology or education fields. It serves as a valuable tool for understanding the cognitive growth and developmental challenges faced by infants and toddlers.

What are Piaget’s key ideas about cognitive development in children?

Piaget emphasized the child's active role in learning, suggesting they learn through exploration and interaction with the environment. He outlined stages of cognitive development, starting from reflexive actions in infancy to more complex problem-solving abilities by toddlerhood.

How does language development tie into cognitive development according to the form?

The form discusses how language development is closely linked to cognitive achievements. As children develop their cognitive abilities, they also learn to express themselves verbally. Initial words lead to two-word phrases, and eventually to more complex language use that reflects their growing understanding of the world.

Can this form support early intervention strategies?

Yes, the Development Lifespan 6Th Edition form includes insights on early interventions for at-risk infants and toddlers. It emphasizes the importance of recognizing developmental milestones so that timely support can be provided, enhancing cognitive and language development outcomes.

How can educators utilize this form in their practice?

Educators can use this form as a reference to guide curriculum design, tailoring learning experiences to meet the developmental needs of children at various stages. It can also inform their understanding of how to support language and cognitive development through play and exploration.

What are the primary theories discussed in the form regarding cognitive development?

The primary theories discussed include Piaget’s cognitive-developmental theory, which focuses on stages of cognitive growth; information processing, which examines attention and memory; and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory, emphasizing the role of social interactions in development.

Where can I find additional resources related to the Development Lifespan 6Th Edition?

For additional resources, you can visit the Pearson Higher Education website or contact your Pearson representative for examination copies. This website also provides updates that may include changes in the publication of the book and further educational materials.

Common mistakes

Filling out forms can often seem straightforward, but when it comes to something like the Development Lifespan 6th Edition form, common mistakes tend to arise. One prevalent error is failing to read the instructions carefully. Many individuals may skim through the guidelines, leading to misunderstandings about what information is required. This can result in incomplete or incorrect entries, which may delay processing or lead to further questions.

Another common mistake involves incorrect data entry. Whether it's a typo in a name, an incorrect date of birth, or misplacing decimal points in numerical entries, these errors can cause significant issues. Such mistakes may result in the need to resubmit the form, wasting precious time. Double-checking all entries before submission can ensure accuracy.

People also tend to underestimate the importance of completing all sections of the form. Omitting a section, even if perceived as minor, can have real consequences. Each component of the form is designed to gather comprehensive information. Failing to address each area can lead to a lack of crucial context or details, ultimately affecting outcomes.

Lack of clarity in writing can present another challenge. When filling out the form, handwriting should be clear and legible. Adopting a rushed writing style or using abbreviations that aren't widely understood might confuse those reviewing the information. Maintaining neatness aids in effective communication and avoids potential misinterpretations.

Finally, there’s often confusion regarding the deadline for submission. Procrastination can lead to submitting forms last minute or missing deadlines altogether. Sticking to a timeline and being aware of all important dates can help prevent any issues that stem from late submissions.

Documents used along the form

The Development Lifespan 6th Edition form is often used in conjunction with various other forms and documents that provide useful information about growth and development. These documents may contain assessments, data collection tools, or guidelines that assist in understanding development across different life stages.

- Assessment Report: This document summarizes the findings from assessments conducted on individuals, detailing areas of strength and development needs.

- Developmental Milestones Checklist: This checklist outlines expected developmental milestones for various age groups, helping caregivers and educators track progress.

- Parent Questionnaire: This form gathers information from parents about their child’s behaviors, routines, and developmental experiences, providing valuable insights for assessment.

- Observation Log: This tool is used to record observations of an individual’s behavior and interactions over time, aiding in identifying patterns and developmental concerns.

- Intervention Plan: This document outlines strategies and activities aimed at supporting an individual's development based on assessment findings.

- Referral Form: This form is used to refer an individual to specialists or services for further evaluation or support in developmental areas of concern.

- Progress Report: This report reviews the individual's growth and progress over a specific period, often summarizing achievements and goals met.

- Service Plan: This outlines the services to be provided for individuals requiring additional support, detailing methods and expected outcomes.

- Feedback Form: This document collects feedback from parents, caregivers, or educators regarding the effectiveness of interventions or programs implemented.

These accompanying documents contribute to a comprehensive understanding of development, facilitating informed decision-making and supportive interventions for individuals at various life stages.

Similar forms

The Development Lifespan 6th Edition form shares characteristics with several key documents in the field of child development. Each document provides insights into different aspects of growth and learning in children. Here are six documents that are similar:

- Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development: This framework outlines the social and emotional challenges faced at different life stages, providing a complementary perspective on how children's cognitive development is influenced by their social environment.

- Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky emphasized the role of social interactions in learning. Similar to the Development Lifespan form, it highlights how cognitive abilities develop within a social context through shared experiences.

- Child Development Milestones: These guidelines specify expected skills for children at various ages. Like the Development Lifespan form, they provide benchmarks for assessing cognitive and language development during infancy and toddlerhood.

- Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory: Both documents present an understanding of cognitive growth. Piaget's theory also describes stages of development and learning processes, aligning closely with the content on cognitive development presented in the Development Lifespan form.

- Theories of Language Acquisition: Various theories explore how children learn language. This is akin to the Development Lifespan form, which discusses the relationship between language development and cognitive processes during early years.

- Baby Learning from TV and Video: This research investigates the effects of media on infant learning. It correlates with the Development Lifespan form’s examination of early cognitive development, considering how children interact with their environments, including media exposure.

Dos and Don'ts

When filling out the Development Lifespan 6th Edition form, consider the following guidelines:

- Do read the instructions thoroughly before starting.

- Do ensure all information is accurate and up to date.

- Do format your responses clearly, using complete sentences where applicable.

- Do provide additional information if prompted or if necessary to clarify your responses.

- Don't rush through the form; take your time to avoid errors.

- Don't use inappropriate language or abbreviations that may confuse the reader.

- Don't submit the form without reviewing all sections for completeness.

Misconceptions

Misconceptions about the Development Lifespan, 6th Edition form can lead to misunderstandings regarding cognitive development. The following list outlines eight common misconceptions and clarifies each point.

- 1. Development follows a strict linear path. Many believe that development moves in a straight line. In reality, development is often irregular, with children experiencing varying rates at different times.

- 2. Infants do not think or learn until they can talk. Contrary to this belief, research shows that infants engage in cognitive processes long before they develop verbal skills. They explore and learn through interaction with their environment.

- 3. Piaget’s stages are rigid and unchangeable. Some assume that children fit neatly into Piaget’s stages. However, children may demonstrate characteristics of multiple stages at once, highlighting the fluidity of cognitive development.

- 4. Early development is solely determined by biology. Many people think that genetics alone dictate cognitive growth, but environmental influences, such as social interactions, significantly shape development too.

- 5. Play is not crucial for learning. There is a misconception that playtime is simply leisure. In fact, play is essential for cognitive, social, and emotional development in young children.

- 6. Children learn best through traditional teaching methods. It’s common to believe structured teaching is the most effective, but children thrive when learning is interactive and exploratory, allowing them to be active participants.

- 7. All children develop at the same rate. Some people think that development milestones apply universally. However, individual differences in growth rates and experiences are normal and can vary widely.

- 8. Intelligence tests accurately capture a child’s potential. Many believe that standardized tests can fully measure a child’s intelligence. Such tests often miss broader aspects of cognitive abilities, such as creativity and problem-solving skills.

Understanding these misconceptions can enhance awareness of the complexities involved in child development, facilitating more effective support for growth.

Key takeaways

Here are some key takeaways about filling out and using the Development Lifespan 6th Edition form:

- Ensure you have the correct edition to prevent any discrepancies in content.

- Carefully read through the instructions provided in the form to understand each section.

- Collect relevant personal information that may be required for accurate completion.

- Utilize the form to track cognitive development milestones, as outlined in the text.

- Reflect on the stages of cognitive changes that are highlighted, particularly in the context of Piaget's theory.

- Consider the developmental activities suggested in the form to engage infants and toddlers effectively.

- Document observations of developmental behaviors accurately to enhance the assessment process.

- Review the relevant theories mentioned in the text, such as Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

- Think about how language development progresses alongside cognitive achievements as you fill out the form.

- Seek guidance from educators or professionals if any aspects of the form are unclear or complex.

Using the form thoughtfully can provide valuable insights into child development and help in creating supportive learning environments.

Browse Other Templates

Formats for Resumes - Key skills necessary for the position are important to address.

Scholarship Application Form,Student Financial Assistance Request,High School Graduate Scholarship,Shelter Foundation Scholarship Application,Local Agent Scholarship Form,Community Scholarship Application,Scholarship Program Enrollment Form,Education - A brief summary of school and community activities must be included.