Fill Out Your Dtsfunctional Additude Scale Form

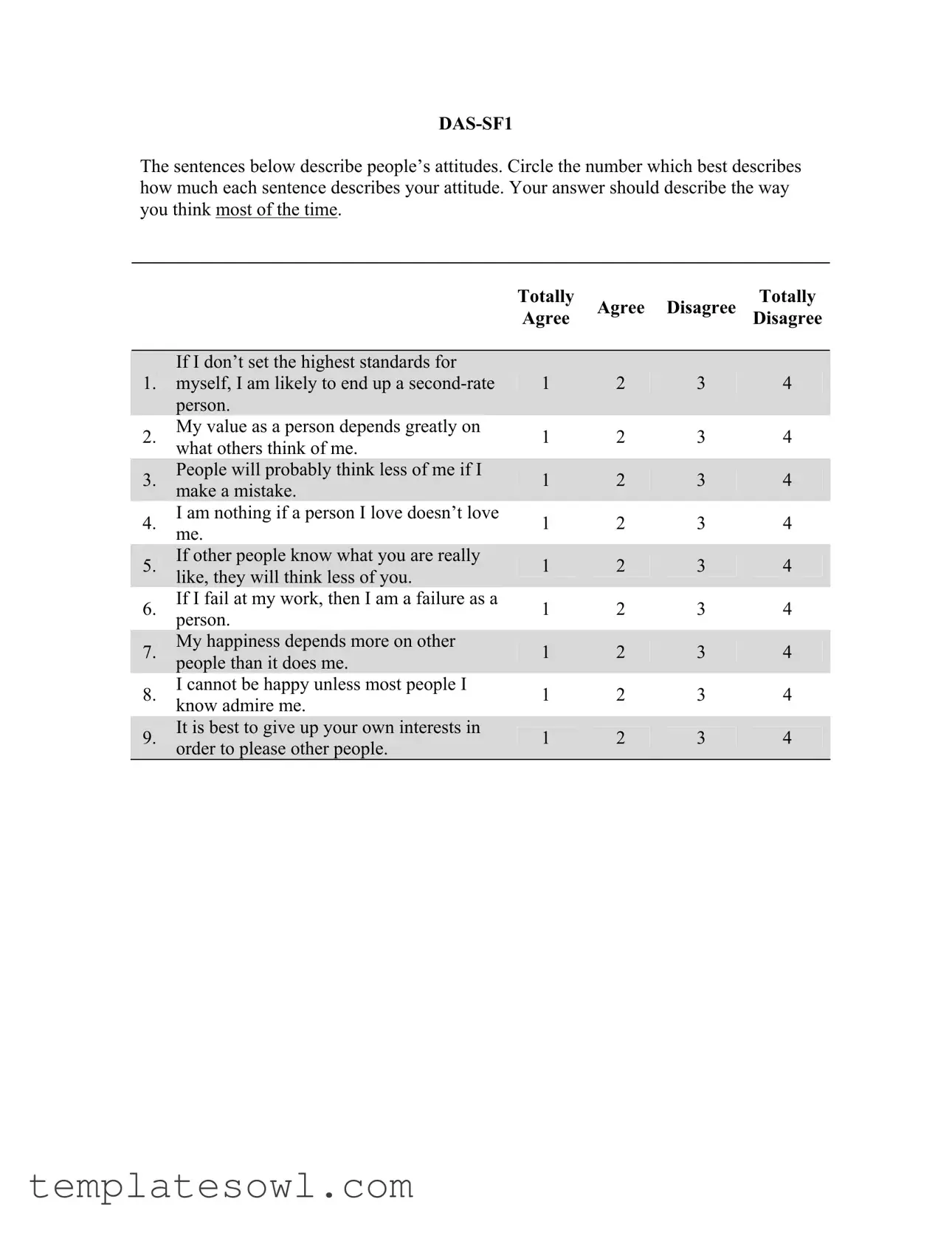

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) is an important tool for understanding the thought patterns that can contribute to depression. This scale evaluates how certain rigid, negative attitudes may affect an individual's mental well-being. The DAS is divided into two short forms, DAS-SF1 and DAS-SF2, which streamline assessment while maintaining robust psychometric properties. Each form consists of statements that respondents rate based on how well they reflect their typical attitudes. The scale covers various themes, such as perfectionism, fear of rejection, and the importance of societal approval. Participants are asked to gauge statements like "My value as a person depends greatly on what others think of me" or "If I fail at my work, then I am a failure as a person," circling the number that best represents their agreement ranging from "Totally Agree" to "Totally Disagree." Through scoring, total results reveal a higher presence of dysfunctional attitudes, shedding light on underlying cognitive distortions that may be contributing to depressive feelings. This assessment is not only essential for research but also serves as a critical component in therapeutic settings, where addressing and reshaping these attitudes can lead to better mental health outcomes.

Dtsfunctional Additude Scale Example

The sentences below describe people’s attitudes. Circle the number which best describes how much each sentence describes your attitude. Your answer should describe the way you think most of the time.

TotallyAgree Agree Disagree DisagreeTotally

If I don’t set the highest standards for

1.myself, I am likely to end up a

My value as a person depends greatly on

2.what others think of me.

3.People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake.

4.I am nothing if a person I love doesn’t love me.

5.If other people know what you are really like, they will think less of you.

6.If I fail at my work, then I am a failure as a person.

My happiness depends more on other

7.people than it does me.

8.I cannot be happy unless most people I know admire me.

9.It is best to give up your own interests in order to please other people.

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

The sentences below describe people’s attitudes. Circle the number which best describes how much each sentence describes your attitude. Your answer should describe the way you think most of the time.

TotallyAgree Agree Disagree DisagreeTotally

If I am to be a worthwhile person, I must

1.be truly outstanding in at least one major respect.

If you don’t have other people to lean on,

2.you are bound to be sad.

3.I do not need the approval of other people in order to be happy.

4.If you cannot do something well, there is little point in doing it at all.

5.If I do not do well all the time, people will not respect me.

6.If others dislike you, you cannot be happy.

7.People who have good ideas are more worthy than those who do not.

8.If I do not do as well as other people, it means I am an inferior human being.

9.If I fail partly, it is as bad as being a complete failure.

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

Scoring

Items should be scored so that total score reflects greater dysfunctional attitudes. This means that most items will be reverse coded. Subtracting 5 from an item score will reverse score that item.

Psychological Assessment |

Copyright 2007 by the American Psychological Association |

2007, Vol. 19, No. 2, 199 |

Efficiently Assessing Negative Cognition in Depression: An Item Response

Theory Analysis of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale

Christopher G. Beevers |

David R. Strong |

University of Texas at Austin |

Brown University and Butler Hospital |

Bjo¨ rn Meyer |

Paul A. Pilkonis |

City University, London |

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center |

Ivan W. Miller

Brown University and Butler Hospital

Despite a central role for dysfunctional attitudes in cognitive theories of depression and the widespread use of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale, form A

Keywords: cognitive, short form, depression, dysfunctional attitudes, item response theory

A central tenet of cognitive theory of depression is that dys- functional attitudes have a critical etiologic role for vulnerability to depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979). Individuals who endorse dysfunctional attitudes are thought to be at increased risk for depression onset (e.g., Alloy et al., 2006; Segal, Gemar, & Williams, 1999). Further, elevations in dysfunctional attitudes are thought to maintain an episode and are often central targets of

intervention during cognitive– behavioral treatment. Consistent with these ideas, numerous studies have observed high levels of dysfunctional attitudes among people diagnosed with unipolar depression (e.g., Dent & Teasdale, 1988; Norman, Miller, & Dow, 1988).

Dysfunctional attitudes are often assessed with the Dysfunc- tional Attitude Scale (DAS; Weissman, 1979). The DAS was

Christopher G. Beevers, Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin; David R. Strong, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, and Addictions Research, Butler Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island; Bjo¨rn Meyer, Department of Psychology, City University, London, London, England; Paul A. Pilkonis, Department of Psychiatry, West- ern Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; and Ivan W. Miller, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University, and Psychosocial Research Program, Butler Hospital.

Research reported in this article was supported in part by several National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants. Research conducted at Butler Hospital and Brown Medical School was supported by NIMH Grant MH43866; Ivan W. Miller was the principal investigator. Research conducted as part of the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program was part of a multisite program initiated and sponsored by the NIMH Psy- chosocial Treatments Research Branch. The program was funded by cooper- ative agreements to six sites: George Washington University, MH33762; University of Pittsburgh, MH33753; University of Oklahoma, MH33760; Yale University, MH33827; Clarke Institute of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, MH38231; and

principal NIMH collaborators were Irene Elkin, coordinator; Tracie Shea, associate coordinator; John P. Docherty; and Morris B. Parloff. The principal investigators and project coordinators at the three research sites were Stuart M. Sotsky and David Glass (George Washington University), Stanley D. Imber and Paul A. Pilkonis (University of Pittsburgh), and John T. Watkins and William Leber (University of Oklahoma). The principal investigators and project coordinators at the three sites responsible for training therapists were Myrna Weissman, Eve Chevron, and Bruce J. Rounsaville (Yale University); Brian F. Shaw and T. Michael Vallis (Clarke Institute of Psychiatry); and Jan A. Fawcett and Phillip Epstein

We thank Aaron T. Beck for allowing us to reproduce items from the original Dysfunctional Attitude Scale.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Christo- pher G. Beevers, Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin,

1University Station A8000, Austin, TX

199

200 |

BEEVERS, STRONG, MEYER, PILKONIS, AND MILLER |

originally a

Studies that have investigated the psychometric properties of the

.59) with each other. Using structural equation modeling, Zuroff, Blatt, Sanislow, Bondi, and Pilkonis (1999) reported that the Perfectionism and Need for Approval subscales had high factor loadings (.87 and .85, respectively) on a common latent variable. These findings suggest that the

Although these studies made important contributions to the development of the

An additional benefit of using IRT to refine the

length of questionnaires could reduce subject burden. Alterna- tively, if subject burden is already minimal, briefer questionnaires could allow for more frequent assessments during treatment with- out substantially increasing subject burden. Repeated assessments are often critical for identifying putative mediators (cf. Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). Finally, psychopathology re- search may also benefit from a shorter version of the DAS, as level of dysfunctional attitudes measured following a dysphoric mood induction is linked to depression vulnerability (Segal et al., 2006). As mood states induced in the laboratory tend to be brief (Martin, 1990), a dysfunctional attitude scale that can be completed quickly may provide an assessment that is more uniformly influenced by a mood induction.

Given the widespread influence of cognitive theory on etiologic and treatment studies of depression (Beck, 2005), the prevalent use of the

To achieve these goals, we pooled data from two treatment studies of unipolar depression: a randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing the efficacy of several treatments among depressed outpatients (TDCRP; Elkin, 1994) and an RCT comparing the efficacy of several depression treatments in the posthospital care of depressed inpatients (Miller et al., 2005). Using IRT methods, we examined the

Method

Participants

Data were pooled from two RCTs for unipolar depression (N 367). The first RCT was the TDCRP. The design and procedures of the TDCRP have been described in detail elsewhere (e.g., Elkin, 1994). A total of 250 patients met study entry criteria and were randomly assigned to treatment; of these, pre- and posttreatment

IRT ANALYSIS OF THE DAS |

201 |

discharged depressed inpatients should allow us to evaluate the performance of the

Measures

DAS (Weissman, 1979). The

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1993). The BDI is a widely used

Cognitive Bias Questionnaire (CBQ; Krantz & Hammen, 1979). The CBQ was used to assess negatively biased,

Hopelessness Scale (HS; Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974). The HS is a

Statistical Model: Overview of Item Response Theory (IRT) Analyses

IRT methods provide a means of scaling both items and persons along a theorized underlying latent continuum of dysfunctional attitudes. These methods assume that individuals vary along a

single latent continuum. Thus, a common factors analysis was conducted prior to IRT modeling. With support for a primary dimension underlying the DAS, we chose to apply a nonparametric IRT modeling strategy to explore the performance of individual DAS items.

Two broad classes of IRT models include parametric (cf. Birn- baum, 1968; Rasch, 1960) and nonparametric approaches (cf. Mokken & Lewis, 1982; Molenaar, 1997; Ramsay, 1991). We chose to use a nonparametric approach to modeling responses to the

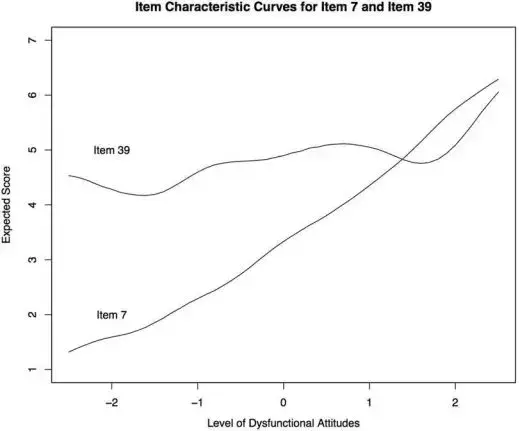

Using a nonparametric approach, we constructed item charac- teristic curves that relate the likelihood of endorsing increasing scores on each item to latent levels of dysfunctional attitudes prior to examining the performance of individual options. We then examined items’ option characteristic curves (OCCs). These OCCs relate the likelihood of endorsing each option on each item to latent levels of dysfunctional attitudes. On the basis of examination of the OCC, items with poor discrimination were identified and dropped from further analysis. Items were identified as having good discrimination if the likelihood of choosing higher options (e.g., “agree very much” vs. “disagree very much”) increased systematically with increasing levels of dysfunctional attitudes. Poor discrimination was identified when higher item options failed to be observed with higher likelihood than lower options despite increases in levels of dysfunctional attitudes. We required that items provide information (e.g., higher options become more likely than lower options) within ranges of the dysfunctional attitudes that would be observed within a significant number of individuals in the present sample

Finally, to explore whether improvements in the efficiency of the

We used a nonparametric

202 |

BEEVERS, STRONG, MEYER, PILKONIS, AND MILLER |

fall closer to the specific evaluation point. We considered items to have good response properties if (a) the probability of endorsing increasingly severe response options increased with increasing levels of dysfunctional attitudes and (b) if curves for at least some of the response options intersected more than once between the 5th and 95th percentiles of estimated dysfunctional attitudes.

Results

Unidimensionality

We conducted maximum likelihood common factors analysis of polychoric correlations for the 40

Item Response Analysis

We next submitted all

After we dropped the 16 items that failed to make multiple dis- criminations, the remaining 24 items were resubmitted to analyses. Although all 24 items appeared to make adequate discriminations, not

Figure 1. Example of one item (Item 7) that performs well in making discriminations throughout the continuum of dysfunctional attitudes. The second item (Item 39) performs poorly, failing to make multiple discriminations within the 5th to 95th percentiles.

IRT ANALYSIS OF THE DAS |

203 |

all response options were making discriminations. Poorly functioning response options could contribute to decreased reliability in rank ordering individual levels of dysfunctional attitudes.

Examining Utility of Response Options

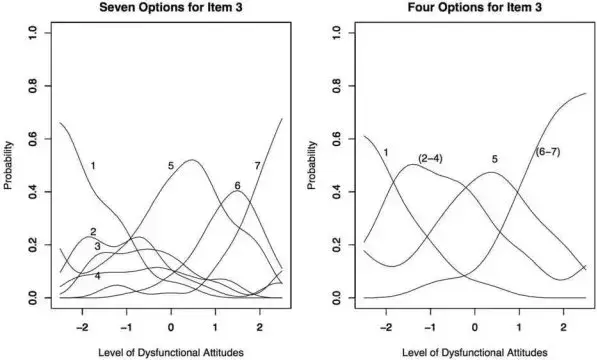

We examined the seven response options to determine whether poorly performing options might be collapsed, as several of the response options were rarely used and were never more likely to be observed than were other options. The OCC for Option 1 (“totally agree”) and Option 5 (“agree”) performed consistently across items, made distinct discriminations, and were clearly more likely to be endorsed than were other options within specified ranges of the continuum. However, several other options did not perform consis- tently. Option 4 (“neutral”) performed quite poorly. It was the least frequently used option (endorsed in 7% of responses), and it was never more likely to be endorsed than was any other option across all ranges of the continuum. Across all items and all levels of dysfunc- tional attitudes, the probability of endorsing Option 3 (“agree slightly”) was always higher than was Option 4 (“neutral”), suggest- ing a reversal in the order of these response categories. Further, Option 2 (“agree very much”) was not consistently more likely than was Option 3 (“agree slightly”). Whereas Option 7 (“totally dis- agree”) did become consistently more likely than Option 6 (“very much disagree”), this option was used infrequently (endorsed in 9% of responses), and the range of discrimination typically was above the 95th percentile. Therefore, on the basis of inspection of OCCs, we collapsed Responses 2– 4 (“agree very much,” “agree slightly,” “neu- tral”) and Responses 6 and 7 (“disagree very much,” “totally dis- agree”). This resulted in

In line with analyses, we labeled the four response options as “totally agree,” “agree,” “disagree,” “totally disagree.”

After recoding, the 24 items were reanalyzed, and OCCs were inspected. As a result of the reanalysis, 6 of the 24 items (Items 6, 17, 23, 26, 27, and 38) failed to make more than one discrimination between the 5th and 95th percentiles and were dropped. The 18 DAS items were retained and again reanalyzed. All 18 items continued to show improved OCCs and continued to make at least two discriminations between the 5th and 95th percentiles. To illustrate the importance of the response format, Figure 2 displays the OCC for Item 3. When allowing all seven options, several of the lower level options (e.g., Options 2– 4) were equally likely within the same range of dysfunctional attitudes and thus could be subsumed within the same option. The OCCs were substantially better when response options were collapsed to form a

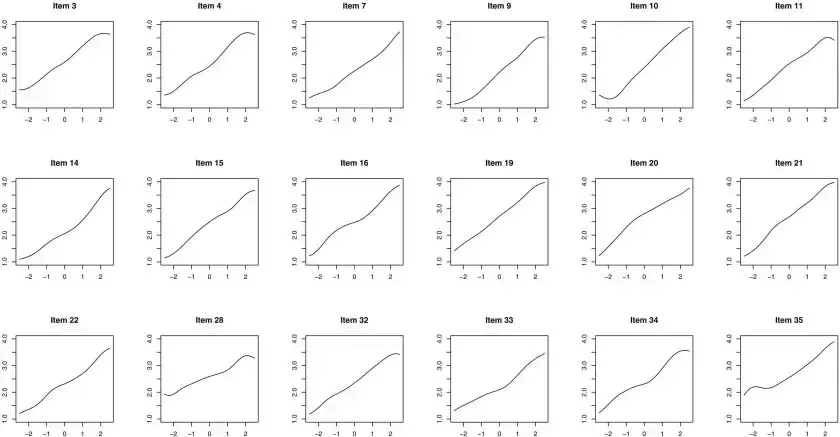

Figure 3 presents the ICC for the 18 remaining

Figure 2. Improvement in scaling response options for Item 3 with a

204

BEEVERS, STRONG, MEYER, PILKONIS, AND MILLER

Figure 3. Item characteristic curves from the 18

|

|

IRT ANALYSIS OF THE DAS |

205 |

Table 1 |

|

|

|

Items Selected for the Short Forms of the DAS Using IRT Methods |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

item no. |

Item |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

1 |

If I don’t set the highest standard for myself, I am likely to end up a |

|

19 |

2 |

My value as a person depends greatly on what others think of me. |

|

3 |

3 |

People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake. |

|

16 |

4 |

I am nothing if a person I love doesn’t love me. |

|

15 |

5 |

If other people know what you are really like, they will think less of you. |

|

10 |

6 |

If I fail at my work, then I am a failure as a person. |

|

34 |

7 |

My happiness depends more on other people than it does on me. |

|

7 |

8 |

I cannot be happy unless most people I know admire me. |

|

33 |

9 |

It is best to give up your own interests in order to please other people. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

1 |

If I am to be a worthwhile person, I must be truly outstanding in at least one major respect. |

|

28 |

2 |

If you don’t have other people to lean on, you are bound to be sad. |

|

35 |

3 |

I do not need the approval of other people in order to be happy. |

|

11 |

4 |

If you cannot do something well, there is little point in doing it at all. |

|

4 |

5 |

If I do not do well all the time, people will not respect me. |

|

32 |

6 |

If others dislike you, you cannot be happy. |

|

22 |

7 |

People who have good ideas are more worthy than those who do not. |

|

9 |

8 |

If I do not do as well as other people, it means I am an inferior human being. |

|

14 |

9 |

If I fail partly, it is as bad as being a complete failure. |

|

|

|

|

|

Note. Analyses indicated that a

the items on the basis of the level within which the item was most discriminating. We then split the 18 items by sorting every other item into a separate

Consistency Within and Between DAS Short Forms

We first examined internal consistency reliability (coefficient alpha) for each short form of the DAS. The alphas were .84 and

.83, respectively, for the

We next examined correlations among these newly formed DAS scales and the original

.85). At posttreatment, similarly high correlations were observed. The

.87) with each other at posttreatment.

We also examined whether the means of the short forms were significantly different from each other at each assessment period. At pretreatment, the

0.38points between DAS short forms was statistically significant (in part due to a large sample size), the effect size indicates that this

difference was small. At posttreatment, the

Change in Dysfunctional Attitudes

We next examined change in dysfunctional attitudes, as assessed by the

t(287) .26, p .79, d .01.1 In addition, these change scores were highly correlated with each other (rs ranged from .84 to .91). This suggests that change in dysfunctional attitudes did not sig- nificantly differ across the DAS forms.

1Degrees of freedom vary slightly due to missing data.

Form Characteristics

| Fact Name | Details |

|---|---|

| Purpose | The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) is designed to assess attitudes that may contribute to depression. |

| Versions | There are two short forms: DAS-SF1 and DAS-SF2, each containing 9 items. |

| Scoring Method | Scores reflect dysfunctional attitudes, often requiring reverse scoring for accurate interpretation. |

| Correlation | The short forms are highly correlated with the original 40-item DAS-A, showing strong consistency. |

| Use in Research | The DAS is frequently utilized in studies examining depression and cognitive patterns. |

| Item Development | Modern item response theory methods were used to refine and develop the DAS short forms. |

| Clinical Relevance | Understanding dysfunctional attitudes can guide cognitive-behavioral treatments for depression. |

| Governing Law | The DAS is subject to psychological assessment regulations, mainly adhering to practices established by the American Psychological Association. |

Guidelines on Utilizing Dtsfunctional Additude Scale

After obtaining the Dissfunctional Attitude Scale form, you will be tasked with assessing your attitudes by rating a series of statements. This will provide insights into your thinking patterns. Carefully consider each statement and choose the response that best reflects your beliefs most of the time. Following completion, your scores can be derived for further analysis.

- Begin with the first section, DAS-SF1. Read each statement carefully.

- For each statement, look at the four response options: Totally Agree, Agree, Disagree, and Totally Disagree.

- Circle the number that corresponds to your response for each statement. The scale is typically assigned as follows:

- 1 for Totally Agree

- 2 for Agree

- 3 for Disagree

- 4 for Totally Disagree

- Once you have completed DAS-SF1, move to DAS-SF2 and repeat the same process.

- When you finish circling your answers for both sections, move on to the scoring section.

- For DAS-SF1, calculate your total score using the formula: Total = (5-DAS1) + (5-DAS2) + (5-DAS3) + (5-DAS4) + (5-DAS5) + (5-DAS6) + (5-DAS7) + (5-DAS8) + (5-DAS9).

- For DAS-SF2, use the formula: Total = (5-DAS1) + (5-DAS2) + (5-DAS3) + (5-DAS4) + (5-DAS5) + (5-DAS6) + (5-DAS7) + (5-DAS8) + (5-DAS9).

- After obtaining your total scores for both sections, review your results to reflect on your attitudes.

What You Should Know About This Form

What is the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS)?

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) is a psychological assessment tool designed to measure negative and rigid attitudes that can contribute to depression. It evaluates how individuals view their self-worth and the influence of external opinions on their happiness. The DAS was developed to help identify these dysfunctional attitudes and is widely used in clinical and research settings related to mental health.

What do the short forms DAS-SF1 and DAS-SF2 consist of?

Both short forms, DAS-SF1 and DAS-SF2, contain a total of 9 items that assess dysfunctional attitudes. Each item presents a statement regarding attitudes, and respondents indicate how much they agree with each statement. These forms are brief yet effective in capturing the essence of the original, longer scales while maintaining high reliability and validity.

How do I score the DAS?

Scoring the DAS involves calculating the total score for each short form. For DAS-SF1, you reverse the score for certain items by subtracting the individual item score from 5, then sum the adjusted scores. DAS-SF2 uses a similar method but retains the score for one item. The final score reflects the extent of dysfunctional attitudes, with higher scores indicating more pronounced dysfunctional thinking.

Who can benefit from taking the DAS?

The DAS is primarily beneficial for individuals experiencing depressive symptoms or those engaged in cognitive-behavioral therapy. It can help therapists identify problematic thought patterns and monitor changes over time. Additionally, researchers frequently use it to understand the link between dysfunctional attitudes and depression, allowing for better-targeted interventions.

How reliable are the DAS short forms?

Research indicates that the DAS-SF1 and DAS-SF2 have strong reliability and validity. More specifically, they maintain a high correlation with the original 40-item DAS. Studies have shown that these short forms provide consistent results, making them effective tools for both clinical practice and research settings.

Can the DAS help in therapy?

Yes, the DAS can significantly aid therapeutic processes. By identifying specific dysfunctional attitudes, therapists can tailor interventions to address these thoughts directly. It serves as a useful diagnostic tool and enables ongoing assessment of an individual's progress throughout their therapeutic journey.

Is the DAS suitable for all populations?

While the DAS has been used successfully with various groups, its design is primarily focused on individuals experiencing depression. Therefore, outcomes may vary based on cultural, socioeconomic, and situational factors. It's essential for practitioners to consider these aspects when utilizing the DAS within diverse populations.

Common mistakes

Filling out the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) can seem straightforward, but there are common mistakes that can lead to misleading results. One frequent error is not reflecting on one’s true feelings. Participants often rush through the questions without considering how they genuinely feel most of the time. This leads to answers that don’t accurately represent their attitudes, thereby skewing the results.

Another mistake is misunderstanding the scale itself. Individuals may circle answers based on what they think they should feel rather than their actual beliefs. For example, someone might mark "Totally Agree" because they believe it’s the socially acceptable choice, even if they do not feel that way internally. This affects the validity of the assessment.

A third common issue involves inconsistent responses throughout the questionnaire. People sometimes circle different answers for similar statements, which can confuse the scoring process. Consistency is key in self-assessments like the DAS, and inconsistency may suggest uncertainty or lack of self-awareness. It’s important to approach each statement separately, giving each one its due thought.

Some people overlook the reverse scoring instructions in the assessment. The DAS is designed so that higher scores reflect greater dysfunctional attitudes. Failing to account for this can lead to incorrect scoring and a misinterpretation of one’s psychological state. Understanding this aspect is essential for accurately applying and interpreting the results.

Lastly, individuals may neglect to answer all items. Leaving questions unanswered can compromise the overall effectiveness of the assessment. Missing responses not only detract from the completeness of the evaluation but can also make it challenging to draw meaningful insights about one’s attitudes. Completing the scale fully allows for a more accurate picture of one’s state of mind.

Documents used along the form

The use of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) often necessitates additional forms and documents to provide a comprehensive evaluation of an individual's mental health status. Below are five commonly associated documents that may be utilized alongside the DAS. Each document serves a specific purpose to enhance understanding of the individual's cognitive and emotional challenges.

- Clinical Interview Form: This document records information gathered during one-on-one interviews with the individual. It helps clinicians understand the patient's background, history, and specific concerns that may not be captured by standardized tests.

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): The BDI is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure the severity of depression. Used in conjunction with the DAS, it helps provide a clearer picture of the individual's mood and emotional state.

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale: This brief scale assesses the severity of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms. Combining results from the GAD-7 with the DAS helps identify potential anxiety-related issues that may be contributing to dysfunctional attitudes.

- Psychosocial Assessment Questionnaire: This tool evaluates an individual’s social support, coping mechanisms, and overall functioning in daily life. It complements the DAS by addressing external factors affecting mental health.

- Progress Notes: Clinicians document ongoing treatment and observations regarding the individual's progress. These notes chronologically track changes in the patient’s attitudes and behaviors, providing key insights into how their mental state evolves over time.

Utilizing these forms and documents alongside the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale facilitates a more holistic understanding of an individual's psychological well-being. This integrated approach enables better-informed treatment plans and supports the overall goal of improving mental health outcomes.

Similar forms

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) form, particularly in its abbreviated formats (DAS-SF1 and DAS-SF2), shares similarities with several other psychological assessment instruments designed to measure self-perceptions and cognitive patterns. Here are five such documents, along with their corresponding similarities to the DAS:

- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): Both the DAS and the BDI assess negative cognitive patterns and self-evaluative beliefs that contribute to depressive symptoms. They are self-report instruments designed to capture the individual's current emotional state and attitudes toward themselves.

- Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ): Like the DAS, the ATQ focuses on identifying negative thoughts and beliefs that can influence a person's emotional well-being. Each item prompts respondents to reflect on their cognitive responses, similar to how the DAS assesses attitudes.

- Cognitive Distortions Scale (CDS): This scale shares the DAS's examination of rigid and irrational thought patterns. Both instruments help to uncover negative self-perceptions that may lead to increased vulnerability to depression.

- Self-Esteem Scale (SES): While the SES primarily measures an individual’s feelings of self-worth, both the SES and the DAS are concerned with how self-perception can impact overall mental health. They encourage individuals to reflect on and quantify their self-expectations and evaluations.

- Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R): This inventory assesses personality traits, including aspects related to emotional stability. Similar to the DAS, it highlights the relationship between cognitive patterns and emotional outcomes, particularly as related to depressive tendencies.

Dos and Don'ts

When filling out the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) form, it is essential to approach the process thoughtfully. Here are four guidelines that can help ensure a productive experience while also highlighting common pitfalls to avoid.

- Do be honest. Reflecting accurately on your thoughts and feelings will provide a clearer picture of your attitudes.

- Do take your time. Carefully consider each statement before circling your answer. This ensures that your responses are well thought out.

- Do remember the aim of the assessment. The scale is designed to measure attitudes that may contribute to feelings of depression or anxiety, so keep this in mind while answering.

- Do check your answers. Once completed, review your responses to ensure you are satisfied with how you expressed your thoughts.

- Don't rush. Hurrying through the assessment may lead to inaccurate responses and a misconception of your feelings.

- Don't ignore the scoring instructions. Understanding how to score your responses is as important as filling out the form, as it affects your overall assessment.

- Don't second-guess yourself. Your first instinct regarding your feelings is often the most accurate, so avoid overthinking each statement.

- Don't stray from the provided scale. Using the response options as intended is crucial for achieving reliable results.

Misconceptions

- Misconception 1: The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) only applies to people with severe depression.

- Misconception 2: The DAS measures intelligence or overall worth.

- Misconception 3: I can answer the scale any way I want without consequences.

- Misconception 4: High scores on the DAS indicate that I must have a mental illness.

- Misconception 5: It's pointless to complete the DAS if I'm not currently feeling depressed.

- Misconception 6: The DAS is too complicated to understand.

- Misconception 7: Results from the DAS should be taken as absolute truths about myself.

- Misconception 8: Once I complete the DAS, I will immediately know how to change my thoughts.

This is not true. While the DAS is often used in clinical settings, it can also assist individuals who are experiencing everyday anxiety or stress. Its aim is to identify patterns of thinking that may lead to negative emotions for anyone, not just those diagnosed with a mental health condition.

Actually, the DAS focuses on specific attitudes and beliefs that can influence one's emotional well-being. It is not a test of intelligence or a measure of a person's overall value. Rather, it identifies harmful attitudes about self-worth and achievement.

While you can respond however you choose, the scale aims to reflect genuine thought patterns. Honest answers lead to accurate results, which can provide valuable insights into how your thoughts may impact your mood and behavior.

High scores indicate a tendency towards dysfunctional thinking, not a diagnosis of mental illness. It helps highlight areas to work on for personal growth and improving mental health, rather than labeling someone as mentally ill.

The scale can be beneficial for anyone, regardless of their current emotional state. Understanding your thought patterns can lead to better mental health and can help you identify potential issues before they escalate into more serious problems.

The DAS is straightforward. It consists of simple statements about beliefs and attitudes. Each statement can be agreed or disagreed with on a scale, making it easy for anyone to use.

While the DAS sheds light on patterns of thinking, it's essential to interpret the results thoughtfully. They are a reflection of attitudes that can change over time, and it's possible to work on these attitudes to foster personal growth.

The DAS can help you identify negative thinking patterns, but changing long-held beliefs takes time and effort. It may be helpful to seek support, such as therapy or counseling, to work through the insights gained from the scale.

Key takeaways

The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) is a tool designed to assess negative cognitive patterns that may contribute to feelings of depression. When filling out and using the DAS, consider the following key takeaways:

- Understand the Purpose: The DAS is intended to identify rigid and negative attitudes. These attitudes can play a significant role in one’s emotional well-being and potential vulnerability to depression.

- Focus on Honest Responses: It is crucial to answer each statement truthfully and reflectively. Your responses should represent how you think most of the time, rather than how you wish to think or how you think in certain situations.

- Coding Process: Familiarize yourself with the scoring system. Most items require reverse scoring, meaning you need to subtract your point selection from 5 to accurately reflect dysfunctional attitudes.

- Consider Each Item Independently: Evaluate each statement on its own. Avoid letting your feelings about one item influence your response to another. Each response should represent a distinct attitude or thought pattern.

- Use the Results Wisely: The total score provides insights into your level of dysfunctional attitudes. Higher scores suggest more prominent dysfunctional thinking, which can be a focus for personal reflection or therapy.

- Seek Professional Guidance: If you find that the DAS indicates high levels of dysfunctional attitudes, consider discussing these findings with a mental health professional. They can help interpret your results and provide support as needed.

- Monitor Changes Over Time: Reassessing your attitudes periodically can reveal important changes. This can be beneficial for tracking progress, especially during therapy or after implementing coping strategies.

- Contextual Understanding: Keep in mind that the DAS is just one tool among many for understanding mental health. Use it as part of a broader approach to self-assessment, which may include therapy, lifestyle changes, or other assessments.

Engaging thoughtfully with the DAS can be a meaningful step in recognizing and addressing negative thought patterns. It encourages self-awareness and opens the door to personal growth.

Browse Other Templates

What Bank Information to Give to Employer Canada - Depositors have the option to include multiple types of currency in their deposit slip.

Dhs 38 Verification of Employment - The employer's response can significantly impact the assistance application outcome.

File a Claim With Allianz - The comprehensive nature of the form supports efficient assessment of insurance needs.